Genetic Factors and Family History

Reviewed by: HU Medical Review Board | Last reviewed: September 2013. | Last updated: April 2019

Experts believe that people who develop RA inherit something in the genes involved in the formation and operation of our immune system that increases the likelihood the immune system will attack healthy tissue in the joints.1

How is genetic risk for RA determined?

Results from genetic studies, including twin studies, family studies, and genome-wide linkage studies, have shown that heritability (or the genetic material that we inherit through our parents and family) definitely contributes to the chances of developing RA. One analysis of data from twin studies found that genetics accounted for over 60% of the overall risk for people who develop RA.2

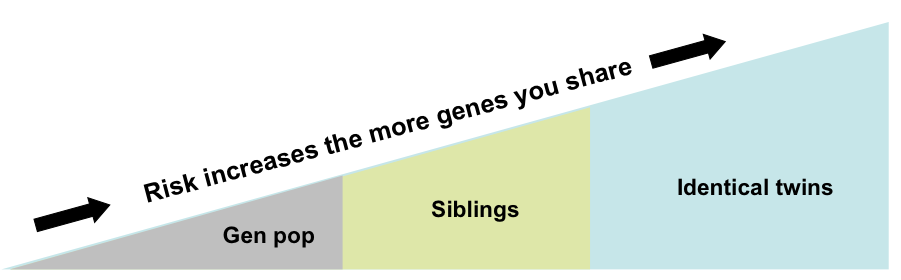

Another way of understanding the influence of genes that contribute to RA is to compare the risk of disease development among groups with differing degrees of genetic similarity. The risk of developing RA in the general population is about 1%. Therefore, about 1 in 100 people in the general population will develop RA. When we look at the chances of developing RA among close family members, such as siblings that share a good deal of genetic material, the risk goes up. The risk of developing RA if your brother or sister (not a twin) has the disease is about 5%. The risk increases further when we consider twins that share the identical genetic material (also called monozygotic twins). If your identical twin has RA, your risk for developing the disease is about 15%.1

Genes and the risk for developing RA

Genome-wide linkage scans

Genetic studies using advanced computer technology to scan the entire genome have been used to identify genetic characteristics (specific variants of genes) that may increase a person’s susceptibility for RA. Only in the last decade have these studies become possible, with the sequencing the human genome and exponential increases in computing power necessary to analyze genetic data. Genetic data from thousands of patients are required to detect any effect in a candidate gene.1

Linkage studies have focused on an area on human chromosome 6 and one area on the short arm of this chromosome called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC, for short) containing hundreds of genes involved in immune system function. Studies have estimated that MHC genes may account for one-third of the genetic contribution to RA risk, more than any other part of the genome. MHC genes with a confirmed role in development of RA include HLA-DRB1 genes, which are thought to be involved in antigen presentation to T lymphocytes. The growing list of non-MHC genes with a possible role in development of RA include the genes PTPN22 and STAT4, which are thought to be involved in T lymphocyte function, the genes TRAF1-C5 and TNFAIP3, which are thought to be involved in tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production and function (TRAF1-C5 is also thought to be involved in complement production), the genes CD40 and PAD14, which are thought to be involved in auto-antibody production (PAD14 is also thought to be involved in citrullination), the gene CTLA4, which is thought to be involved in T lymphocyte activation, and the IRF5 gene, which controls macrophage-promoted inflammation.1,2

Selected genes thought to increase susceptibility for RA

Adapted from Plenge RM. The genetic basis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatoid Arthritis. Philadelphia, Penn: Mosby Elsevier; 2009:23-27.

Genetic risk and auto-antibodies

In RA, the immune system malfunctions and turns against the body’s own healthy joint tissue. As part of the autoimmune response in RA, the immune system develops auto-antibodies against healthy tissue. This is similar to how in the normal immune response, the immune system develops antibodies against foreign organisms (such as viruses) that invade the body. Recent research has shown that RA can be divided into subtypes according to the auto-antibodies that are found in RA joint tissue. These subtypes are referred to as ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative RA. ACPA is short for anti-citrullinated protein/peptide antibody, which refers to a particular kind of antibody designed to attack proteins that have undergone a process called citrullination, which happens in response to inflammation.4

It turns out that among the gene variants associated with RA, some are associated with ACPA-positive RA and others with ACPA-negative RA. ACPA-positive RA is associated with certain gene variants, including HLA-DRB1 SE, PTPN22, TRAF1-C5, CTLA4, STAT4, while ACPA-negative RA is associated with gene variants, including HLA-DRB1 DR3 and IRF5.4

Newer genome-wide association studies

Recent advances in computing have made it possible to test for small genetic variants across hundreds of thousands of genes. Results from these new genome-wide association studies promise to expand the list of genes known to increase susceptibility to RA and advance our understanding of the genetic mechanisms involved in the pathology of RA.1